At Crate Free USA, our mission is to improve the lives of animals raised for food. And since the vast majority of Americans still eat meat, the best way to do this is to shop from local farmers who care about the animals they raise far more than the huge factory farms and corporations who own so much of the food industry today. While we do promote a reduction of meat in your diet, we also support our local farmers who raise animals more humanely and sustainably.

It’s easy for you to find a local, sustainable farmer near you in Illinois.

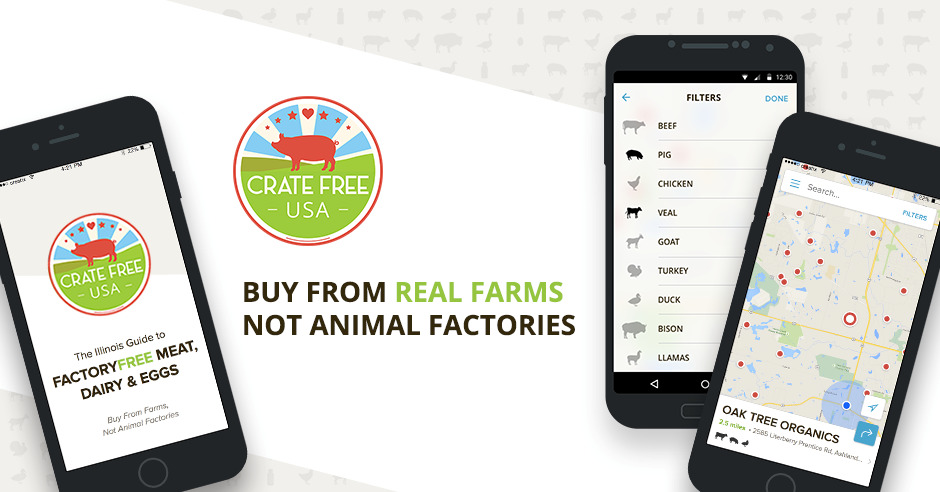

Just download our free mobile app!

We caught up with David and Susan of Kinnikinnick Farm.

Here’s their bio in their own words:

In 1992, David and Susan Cleverdon sent their last child off to college, sold their Hyde Park co-op apartment in Chicago, put all their belongings in storage, and moved into a house trailer on an abandoned farm, which they’d purchased five years earlier. Over the years they reclaimed the farm, restored its buildings, and built a diversified farming business based on poultry, pork, produce, and a family FarmStay hospitality business.

In addition to farming, David was a founding member of both the Frontera Farmer Foundation and Chicago’s Green City Market.

David and Susan at Kinnikinnick Farm

Farming is David’s third gig.

He has an MA in history from the University of Chicago where he was a PhD candidate until he wandered off the academic reservation into the civil rights movement where he became an organizer. In 1964, he went to Mississippi and helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. He returned to Chicago and organized the political field organizations that sent Abner Mikva to Congress and Dan Walker to the Governorship of Illinois. He served on the staffs of both men and became the executive director of the Illinois Democratic Fund.

In 1977, he left politics for the world of finance and trading. He joined the firm, Stotler and Co., at the Chicago Board of Trade where he became the Division Manager of Stotler’s Financial Futures, Metal, and Currency Division, a floor trader, and publisher of a financial newsletter. From 1988 to 1992, he ran the Illinois State Treasurer’s Link Deposit Program for Economic Development.

Susan graduated from Harvard University in 1965. Her background is in sales and fund raising. Before moving to the farm, she was an active member of Chicago’s Hyde Park Community where she raised the family and sold real estate. When she and David moved to the farm, she accepted an off farm job and became the Major Gifts Officer and Director of Planned Giving at nearby Beloit College.

Tell us about your farm:

Kinnikinnick Farm is a 46-acre smallholding, two miles south of the Illinois-Wisconsin State line and five miles east of the I-90 Interstate.

Annually, we raise 1,500-2,000 broiler chickens, keep a laying flock of 300 hens, feed out Berkshire feeder pigs, maintain a small market farm vegetable garden, manage a few bee hives, keep a small herd of dairy goats, and live with three farm dogs and nine cats.

We started out in 1994 as a certified organic produce farm selling to Chicago restaurants and at farmers markets. We still do a small produce business. But most of our vegetable beds have been converted to pasture and hay fields. Our livestock is raised on pasture. From the start, we have tried to follow Walter Goldstein’s advice to “keep it green, all the time.”

In 2017, we dropped our organic certification and adopted AWA (Animal Welfare Approved) standards for humane livestock handling. We are more concerned about animal welfare than organic purity. Our laying flock is AWA certified.

The goats are a key part our fertility program.

How did you first become involved in farming?

I blame Wendell Berry, New Farm magazine, and a backyard garden that grew and grew until it got so out of hand that I said to Susan one day, “We don’t need a garden. We need a farm.”

In September 1987, we bought a farm. At that time farmland was cheap. Prices had collapsed to less than 25 cents on the dollar due to high interest rates.

The farm we bought was a rundown corn and bean farm with an abandoned farmstead on the north bank of the Kinnikinnick Creek in Boone county. The farmhouse was partially collapsed. The outbuildings were falling down. There were piles and piles of garbage and metal junk everywhere, and impenetrable thickets of tall, man-eating weeds. It took us five years of weekends to clean it up enough to get a foothold. Through it all, we had a dream of the small commercial farm we wanted to create.

Why is farming sustainably and humanely important to you?

It’s the only way small farms can thrive and succeed. And we think the expansion of successful rural small farms is important—economically, socially, culturally–for the future of our country.

How have the economics of farming changed in the last several years and how has it affected you?

Three events changed the fundamental economic life of Kinnikinnick Farm. The opening of the Green City Winter Farmers Market in 2008. The Late Blight Pandemic in 2009. The COVID pandemic of 2020.

The winter farmers market made it possible for us to add livestock to our farming mix. We could farm and be in business year-round instead of being tied to that intense April-October vegetable production sprint. Our income rose and our stress level dropped.

The 2009 Late Blight almost put us out of business. We watched an acre of tomatoes die over a weekend. We diversified. We reduced our reliance on produce, added more livestock, and started a FarmStay hospitality business.

COVID shut down restaurants and farmers markets. Overnight, we became an e-commerce marketing farm. Our customers could buy meat, eggs, and seasonal produce on-line, pay on-line, and drive by one of our pickup sites, pop their trunks, and get their order while maintaining social distance. E-Commerce fits what we do. We don’t plan to go back to restaurant sales and farmers markets.

What further changes are you anticipating?

We are expanding our e-commerce marketing. We expect to be doing home delivery (Fedex/UPS) by the end of the year and are already including production from other local farms.

What are your views on extreme confinement and gestation crates for pigs? Would you support a bill to ban extreme confinement? Why or why not?

Where to start?

Yes, we would support a ban on extreme confinement and gestation crates. In fact, last week I called our two senators urging them to vote against including the EATS act or anything like it in the Farm Bill.

Livestock confinement is part of modern agriculture based on fixed cost, energy intensive, single purpose assets. Yes, it is efficient. But it comes with a cost: it is inherently unstable. I can’t change and adapt quickly. We saw a glimpse of that during the pandemic when supply chains were interrupted and store shelves emptied out.

We would be more comfortable with a more decentralized, more resilient agricultural system based more on management smarts than on highly capitalized fixed costs, a system more able to adapt and change to withstand the shocks that are coming: more global warming, more supply chain disruptions. Mass migration, etc.

On top of that extreme confinement and gestation crates are just plain unethical. They violate the five livestock freedoms that are the foundation for humane animal husbandry and that, at the end of the day, produce a better product.

What is your current slaughter process?

We use small, local, family-owned USDA inspected processing plants: Twin Cities Packing in Shopiere, WI for chickens; Lake Geneva Country Meats and HomeTown Sausage Kitchen for Pork; Eickman’s Processing Co. for the grass fed/finished steers we buy from a local grazier to make our all-steer ground beef.

What can consumers do to help improve the lives of all our farm animals?

Become so aware of, and educated about, the brutality of factory farming that opposing it in every way becomes a necessary, existential act.

How do you market and sell your products? How can people shop with you/find you?

We market and sell online.

It’s as simple as 1,2,3. Go to kinnikinnickfarm.com. Open an account. Place an order. Pick up your order at one of our drop sites listed on our website, or at the farm.

Can people visit the farm?

Sure. Just call ahead. Late afternoons on weekdays are best. We have a farm full of FarmStay families here on weekends. Most of them are families that have been coming here for a three-day weekend visit every summer for years and years.

We live in Rochelle Illinois and just heard of you.