Efforts to bring more humane treatment of farm animals recently received a huge boost with the announcement that the Humane Society, the nation’s pre-eminent animal welfare organization, has established a State Agriculture Advisory Council in Illinois.

Mission of Agriculture Councils

The mission of these councils, composed primarily of family farmers and ranchers who practice and promote higher animal welfare standards, is to provide assistance to others within their individual states who wish to change their operations in ways that are more humane for the animals in their charge and are, at the same time, more environmentally responsible. Additionally, the state councils provide guidance and advice to the Humane Society as that organization continually assesses and re-assesses every aspect of the care of farm animals from birth to death.

Source: pixabay.com

The Illinois council consists of five to 10 active members, people like: Cindy Arnett from Arnett’s Acres, a small family farm of 120 acres, Cliff McConville from All Grass Farms, a diversified family farm, and Dave Bishop of PrairiErth Farms, whose 300 acres Dave and his family have tended to for over 30 years.

With the addition of Illinois, there are now 12 states that have already established their own councils. Ultimately, the Humane Society hopes and expects to have councils in all fifty states. Currently, ag councils exist in Colorado, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, the Pacific Northwest and Nebraska, the state in which the Humane Society established the first ag council in 2011.

With the addition of Illinois to that list, Minnesota becomes the only one of the top pork producing states to not have an ag council. This is important in that pork production is highly concentrated, both in the states in which it is a major industry and in the size of the individual facilities.

National Agricultural Advisory Council

To coordinate the work of the various state councils and share in the information and experience they garner, a National Agricultural Advisory Council was established in 2016. This organization is made up of “distinguished farmers and ranchers” who are “proven leaders who represent the face of humane and sustainable agriculture in this country” and who’s mission is “to improve the welfare of farm animals in a way that benefits not only the animals, but the farmer, the consumer, and our environment,” said Kevin Fulton, the council’s first chairman.

Ag Council Reception

Not surprising to those of us who have been active in efforts to, at least in some small measure, improve the horrific, barbaric conditions in which farm animals spend virtually every moment of their terribly short lives, these councils have not been well received by some entities which control American agriculture; the huge corporations that dominate the supply of meat and poultry from birth to death and then on to your local supermarket.

Arguments levelled against these ag councils and the Humane Society fall in two broad categories:

First, there are misrepresentations of the very nature of the Humane Society and its goals so severe that they could be characterized as libelous. These arguments posit that the Humane Society has a hidden agenda to “limit and eventually end animal agriculture.” This quote is from a group called Animal Ag Engage. It is a refrain often repeated by supporters of the pork industry’s current practices. This, of course, is simply not true; according to Wayne Pacelle, former CEO of HSUS, the majority of HSUS members are not vegetarian.

Other similar attacks are that the “HSUS cares first and foremost about lining their own pockets, and their second greatest mission is to abolish all animal agriculture.” That came from Wayne Prescott, Vice President of the Idaho Cattle Assn.

The second argument is a little more serious on its face, but with only modest inspection, it is apparent on multiple fronts that this is nothing more than the disingenuous pronouncements of an industry trying to justify the unjustifiable.

According to this line of reasoning, farmers don’t have to join councils, they know that they have to be good stewards of the land and the environment because their livelihood depends on it. Besides, they want to leave the land better for future generations.

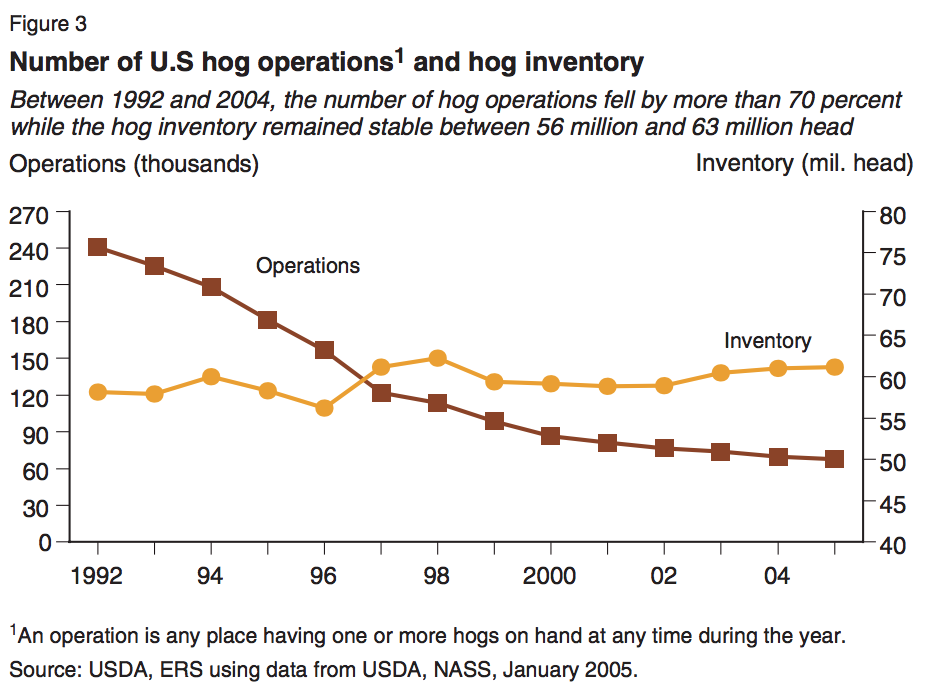

Clearly, this argument against the need for ag councils completely misses the point; these arguments do not even address the plight of the animals at all! Even disregarding that rather important point, there is the additional problem that this case depends on a completely false narrative; the family farm is an inconsequential player in the supply of pork to the commercial marketplace. Author Barry Estabrook in his book, Pig Tales, estimates that 97% of pork in the United States is from pigs who have suffered in crates, the vast majority of which are on large factory farms. Despite ever increasing consumption, the number of hog farms in the United States has been decreasing steadily for decades resulting in each individual factory operation to increase in size.

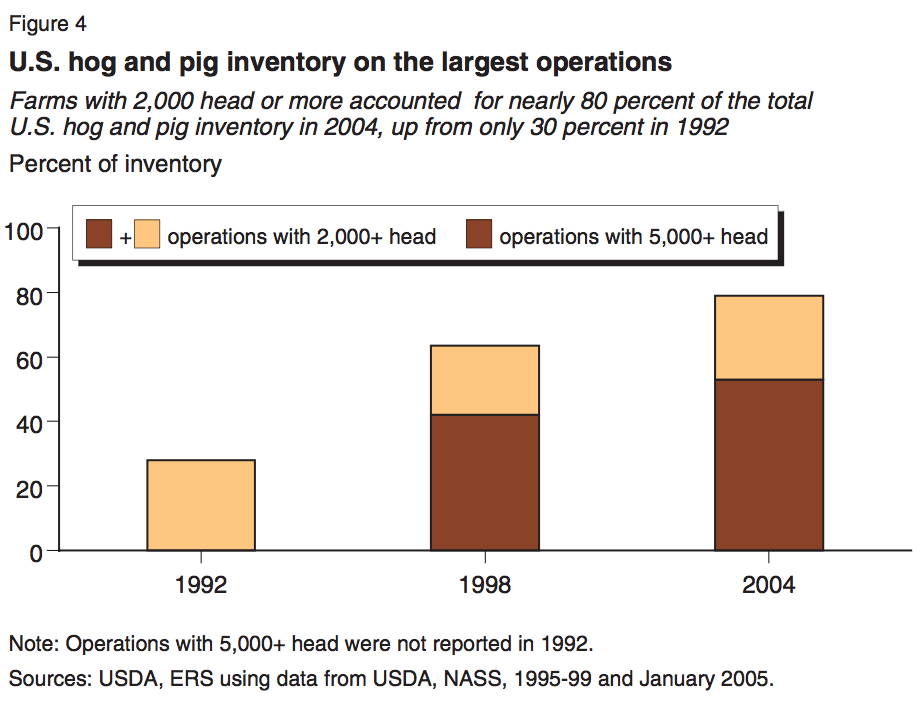

The number of hog farms fell by more than 70 percent between 1992 and 2004, from over 240,000 to fewer than 70,000. But during that same time frame, the share of the U.S. hog and pig inventory on farms with 2,000 head or more increased from about 30 percent to nearly 80 percent. In 2004, farms with 5,000 head or more accounted for more than half of all hogs and pigs. [see the full USDA report here]

Therefore, the argument that these “farms” are good stewards of the environment who we can trust to take good care of the animals in their charge is a myth; it is an image of an America that existed long ago, long before many of us were born. Pork is now produced largely by large corporate entities whose top concern is how much money they make. That means margins; producing as cheaply as possibly and selling as much as possible.

Why Ag Councils are So Important

Therein lies an important reason for ag council’s to exist; it allows those smaller producers and whichever larger ones happen to join them to share, teach and learn from one another. The use of hoop housing for pigs, for example, is being tried in a number of areas with promising results.

Sharing those experiences can go a long way towards bringing about more environmentally friendly, more resource efficient, and more humane methods of raising the food we eat. The more efficient responsible farmers can make their operations, the less disparity there will be between inhumanely raised, antibiotic laden meat and meat that was, at least, not raised in crates. And, presumably, more consumers will then make the right choice.